From research lab to hospital ward Guy Maddern is always on call

Professor Guy MaddernDespite the demands of an ageing population and huge expectations on public hospitals, South Australia can meet the emerging health challenge, says Professor Guy Maddern.

And none are better placed to assess what the state needs to do and how the University of Adelaide can help it happen. Professor Maddern has four degrees from the University, where he has worked for over 20 years. He is concluding work this year on three major National Health and Medical Research Council projects and completed an Australian Research Council funded study on surgical innovation in 2014.

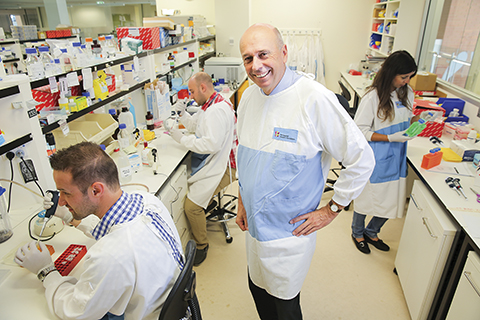

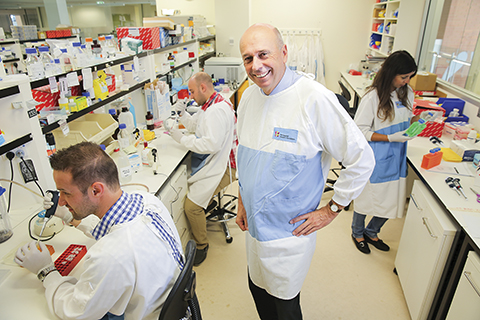

Among his day jobs, Professor Maddern is a Professor of Surgery at the University of Adelaide, Director of the Discipline at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and a Clinical Director at the Central Adelaide Area Health Service. He is also Head of Research at the Basil Hetzel Institute (BHI), the research arm of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. The Hospital is a major teaching venue for the University’s School of Medicine.

It all combines to give him a system-wide insight and keeps him focused on what research is accomplishing and what it could do with more resources.

It’s a huge role burdened with life and death responsibilities. And yet Professor Maddern remains a pragmatic optimist, aware that Australian medicine does well, but conscious of what it can do better.

He certainly believes the University’s researchers are performing well above world standard.

The BHI, named after prominent South Australian medical researcher Basil Hetzel, has a $21m annual research budget and is 90 per cent occupied by University of Adelaide staff and students. “We have masters to post-doctoral people working across the spectrum of clinical research,” Professor Maddern says.

“Much of our work is around cancer, managing, identifying, destroying tumours in ways that don’t require mutilating invasion. We like timely treatment that gets patients home quickly,” Professor Maddern says.

“When I was training in the 1970s, patients aged over 100 were exceptional. Now they are far more frequent – many are frail but they are ‘with it’, and do well,” he says.

However even with increasing demands from an ageing population he is optimistic that the challenges can be met.

To control cost increases and improve productivity he points to information, education and expectations as the issues that shape the future of care.

Professor Maddern also says the profession must look at the way doctors are initially educated. “Students need to have more focused experiences.” He points to close contact with GPs and rural placements as “very positive” examples of what is important.

And then there are the assumptions medical professionals and patients make about appropriate care.

“The Australian health system has to look at whether we add value to care and treatment – we should not just do things because we can,” he says.

However age is not an inevitable arbiter of what treatments are appropriate. “We operated last week on an 84 year old with liver cancer. Lots of patients like this not only survive surgery but go home and continue to lead productive lives,” he says.

In the end it seems, there is a lot to like about the way Adelaide manages hospital care. “There is good evidence we use more acute beds than comparable environments – then again the United States has very short hospital stays and it spends a higher share of GDP on health.”

|