Adopt-a-Book

An Initiative of the Friends of the University of Adelaide Library

The compleat statesman: or, The political will and testament, of that great minister of state, Cardinal Duke de Richilieu. From whence Lewis the XIV, the present French-King has taken his measures and maxims of government.

Armand Jean du Plessis Richelieu (1585-1642)

London: Printed for R. Bentley, 1695

Rare Books & Special Collections

Strong Room Collection SR 944 R52

We thank our donor...

Conservation treatment of The compleat statesman... was generously funded by Adopt-a-Book donor, Bryce Saint. His valued contribution has ensured this rare political testament will be available for future generations of researchers for many years to come.

Synopsis

Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu was a French clergyman, nobleman and statesman. His father, soldier and courtier François de Plessis, died when Richelieu was just five, fighting in the French Wars of Religion. His mother, Susanne de La Porte, also came from a prominent family, her father a famous jurist. As a young boy, Richelieu was educated at the College of Navarre in Paris, where he studied philosophy. He later applied himself to military training but his plans were cut short when the family was granted bishopric of Luçon. A reward for François’ contribution to the war, they quickly became accustomed to appropriating its revenues for personal use. They were continually challenged, however, by clergymen who wanted the funds for ecclesiastical purposes. So, Richelieu’s mother, in an attempt to secure the earnings, proposed to make her second son the Bishop of Luçon. He did not desire the bishopric, however, and became a Carthusian monk instead, leaving Richelieu to study for the post.

In 1607 Richelieu was consecrated Bishop and was soon heralded as a reformer, becoming France’s first Bishop to implement the institutional reforms prescribed by the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563. The clergymen of Poitou asked Richelieu to be one of their representatives to the States-General in 1614 and from there, his political career grew. A staunch advocate for the Church, Richelieu argued that it should be exempt from taxes and that bishops should be given more political power. He faithfully served Concino Concini, one of the most powerful ministers in the Kingdom and the Queen Mother’s favourite, and by 1616, he was made Secretary of State and given responsibility for foreign affairs. Like Concini, he became a close advisor of King Louis XIII’s mother, Marie de Médicis, who effectively continued to rule when her nine-year-old son, Louis, ascended the throne. Her policies, and those of Concini’s, were not popular, and in 1617 their powerful enemy, Courtier Charles de Luynes, hatched a plot to have Concini arrested and killed should he resist. He was consequently assassinated and Médicis overthrown and confined. As quickly as Richelieu’s political influence had risen, he lost it. The death of his patron left him powerless; he was dismissed as Secretary of State, removed from the court, and ultimately banished to Avignon by a King who remained suspicious of him.

In 1619 Médicis escaped from her confinement and became the leader of an aristocratic rebellion. Believing Richelieu might be able to reason with the Queen, the King and de Luynes recalled him from Avignon, where he had been passing the time writing. Mediating negotiations between the Queen and her son was fraught with complexities but Richelieu was successful and in August the Treaty of Angoulême was signed, essentially ending the civil war in France between the Queen’s and the King’s supporters. Just two years later, de Luynes died and Richelieu quickly rose to power again when the King nominated him for a cardinalate which was granted in 1622. Crises such as the rebellion of the Huguenots in France soon rendered Richelieu an indispensable advisor to the King, and by 1624 he was appointed to the royal council of ministers. Just five years later he became the King’s chief minister, when the incumbent at the time, Charles duc de La Vieuville, was arrested for corruption.

As chief minister Richelieu had two main goals – centralise power in France and oppose the Hapsburg dynasty which was ruling in Spain and Austria. His methods for achieving those goals were not always popular. On the one hand, he offended most of the feudal nobility in attempting to suppress their influence, abolishing the position of Constable of France and ordering the destruction of all fortified castles which were not needed to defend against invaders. On the other hand, he upset most of the peasants by raising taxes from which most of the nobility, clergy and high bourgeoisie were exempt. The result was multiple uprisings, all of which Richelieu crushed, dealing with rebels harshly. There were others, still, who he managed to vex. By openly aligning France with Protestant powers, Richelieu was denounced by many as a traitor to the Roman Catholic Church. The Country’s military battles were disastrous, with many early victories going to the Spanish Empire, and conflict lingered on for a number of years after Richelieu’s death.

Despite his ability to alienate people, Richelieu had many successes. Though he did not survive to the end of the Thirty Years’ War, he was instrumental in redirecting the conflict between Protestantism versus Catholicism to nationalism versus Hapsburg dominance. Over time, France essentially depleted the resources of the Hapsburg Empire, virtually to the point of bankruptcy. By 1648 the Hapsburg forces had been overcome and their failure to prevent the French from invading Catalonia, Spain, ensured the end of the Hapsburg power of the continent. King Louis XIII’s successor, King Louis XIV, continued Richelieu’s work, enacting policies that further suppressed the aristocracy and destroyed all remnants of Huguenot political power. In fact, many of Richelieu’s policies provided the foundation for Louis XIV’s success as a Monarch, and by the late 1600s France had arguably become the most powerful nation in all of Europe. Richelieu’s aggressive foreign policy and aim for a strong nation-state were to shape the modern system of international politics familiar to us today. Certainly, concepts of national sovereignty and international law can, in part, be traced back to his policies, particularly as declared in the treaties of Westphalia, which largely brought to an end the horrific European wars of religion.

Richelieu was also an important patron of the arts. He was the founder of the Académie française, France’s official authority on the usages, vocabulary and grammar of the French Language. He enjoyed the theatre, funded the literary careers of numerous writers, and his own impressive library, consisting of some 900 manuscripts alone, he left to his great nephew on the proviso that it was not merely for the use of family but that it should be open, at fixed hours, to scholars. He also oversaw the construction of his own magnificent palace, Palais-Cardinal in Paris, renamed the Palais Royal after his death, which now houses the French Constitutional Council and the Ministry of Culture.

The Library’s copy of The compleat statesman… is the fourth impression, printed in 1695. Its ‘Advertisement to the Reader’ suggests much of its content is derived from a manuscript by Cardinal de Richelieu, with only the most obvious of faults corrected “for fear of mistaking the sense of the Author”. It is essentially a history of the “glorious successes” of King Louis XIII, with the book’s first chapter dedicated to great battles. Aptly titled “A short relation of the King’s great Actions, until the Peace concluded in the Year_____”, its blank line suggests that there existed no general peace at the time of writing. The second chapter, “Of the Reformation of the Ecclesiastical Order”, considers the ill state of the church at the beginning of the King’s reign as well as its present state, including Richelieu’s thoughts on the characteristics of a good Bishop. Chapter three outlines the importance of respect for the Nobility, who had been “so much depress’d of late Years by the vast Number of Officers”, whilst chapters four and five discuss topics such as the “defects of the Courts of Justice” and the “Incroachments of some Officers” upon the “First Rank”, otherwise known as the church. The need for the King to follow the will of his Creator and submit to His laws, if he wished his own subjects to obey his orders, is the message of chapter six and the state of the King’s household, whether it be the necessity for “Neatness”, “Magnificence of Furniture” or “great Horses”, forms the basis of chapter seven.

It is in the final chapter (eight) though, where we really begin to appreciate the significance of the book’s title. Here, Richelieu muses: “In a word, A States-man must be Faithful to GOD, to the State, to all Men, and to himself; which he will be, if, beside the Qualities above-mention’d, he has an Affection for the Publick, and has no private Ends in his Counsels… The Integrity of a Counsellor of State must be active; it disdains Complaints, and fixes on solid Effects, which may be useful to the Publick”. Ultimately, Richelieu argues: “As the Integrity of a Counsellor of State requires his being proof against all sorts of Interests and of Passions, it also requires his being so against Calumnies; and that all the Crosses he may meet with, may never discourage him from doing well.”

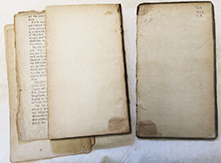

Original Condition

Calf spine with original blue paper sidings. Spine and board corners severely bumped. Front and rear boards completely detached. Textblock split in two, with front endpaper and front free endpaper also detached. Tears to multiple pages, including title page and 'Advertisement to the Reader'.

|

|

|

|

|

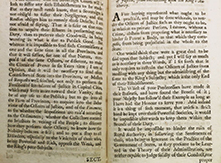

Restoration by Anthony Zammit

Front and rear boards reattached using custom-dyed brown Japanese repair paper along the outer joints and cream-coloured Japanese repair paper along the inner hinges. Front endpaper and front free endpaper tipped back in and open tears to both repaired with Japanese repair paper. Tears along both title and the 'Advertisement to the Reader' page edges also repaired with Japanese paper. Textblock resewn, joining the two split halves together again.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lee Hayes

October 2018