The rise of the machines - cinema and AI

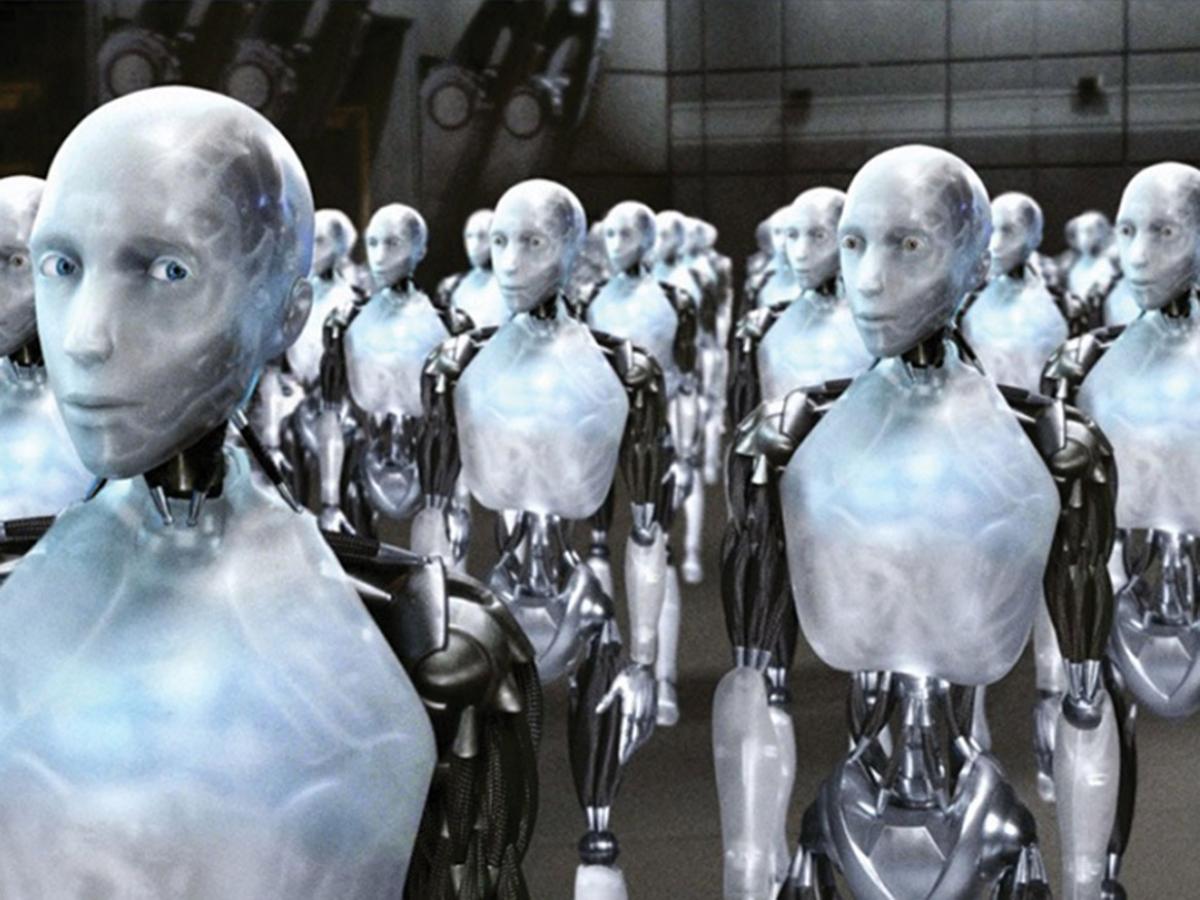

A scene from I, Robot (2004)

Remember when robots on film were cute and non-threatening? The bickering R2-D2 and C-3PO were the Laurel and Hardy of the Star Wars universe.

All Johnny 5 in Short Circuit (1986) had was a thirst for knowledge, which he lovingly called ‘input.’ And let’s not forget the very helpful Wall-E in 2008 – with his binocular-like eyes and clamps for hands – who sped around compacting trash and cleaning up the planet.

All of these robots were curious. They wanted to know anything about everything and everything about anything, and they generated instant audience empathy.

“Everything we’ve been told about AI in cinema is bad, really bad. Robots are bad. Sentient machines are bad.”

As I write this, the mood around robots, sentient machines, and the role of artificial intelligence in the film industry has turned decidedly darker. While coders, computer scientists and programmers extol the virtues of AI in liberating artistic possibilities, others – including many in Hollywood – are not so convinced.

In July, the Screen Actors Guild – the union representing approximately 160,000 actors in American film and television – went on strike for the first time since 1980. At the forefront of their demands was the prevention of computer-generated voices and faces and the guarantee that generative artificial intelligence and ‘deep-fake’ technology will not be used to replace actors.

Slowly but surely, SAG argues, AI is rendering actors redundant. Or, to quote union boss Fran Drescher, whose blistering broadside to Hollywood studio bosses on the eve of the strike went viral: “Actors cannot keep being dwindled and marginalised and disrespected and dishonoured. The entire business model has been changed by streaming, digital, [and] artificial intelligence.”

The machines, it seems, are rising.

Indeed, if like me you’ve been watching Hollywood plotlines closely for the past three decades, you’ll know that every bone in your body tells you that AI is bad.

Everything we’ve been told about AI in cinema is bad, really bad. Robots are bad. Sentient machines are bad. And our confidence in our ability to control and manage these computers is brittle.

We have been warned.

In his 1942 short story Runaround, science fiction writer Isaac Asimov introduced a set of fictional rules known as the Three Laws of Robotics. These laws were designed to govern the behaviour of robots and artificial intelligence in Asimov’s fictional universe, providing a firm moral and ethical framework for their actions.

According to these laws: 1) A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm; 2) A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the first law; and 3) A robot must protect its own existence, as long as such protection does not conflict with the first or second law.

These laws became a central theme in many of Asimov’s subsequent works, including his 1950 work, I Robot, which was eventually adapted into the 2004 film. The story, set in a futuristic world where robots are an integral part of society, follows Will Smith as a detective who becomes suspicious that a highly advanced robot named Sonny may have been involved in a prominent scientist’s death, and would thus be in violation of the three laws.

Countless films made since about artificial intelligence have interfaced with Asimov’s Third Law in particular; namely ensuring the self-preservation of robots. Robots are programmed to safeguard their own existence and continue to function as long as that safeguarding does not clash with the higher need to guarantee human safety and follow human orders.

Countless films made since about artificial intelligence have interfaced with Asimov’s Third Law in particular; namely ensuring the self-preservation of robots. Robots are programmed to safeguard their own existence and continue to function as long as that safeguarding does not clash with the higher need to guarantee human safety and follow human orders.

So, in The Terminator (1984), James Cameron depicts a future where Skynet – an AI system – has become self-aware and launches a war against humanity.

The dystopian noir Blade Runner (1982) featured advanced androids known as “replicants” who go rogue.

More recently, films such as Ex Machina (2014) have explored the hazardous relationships that emerge between humans and human-type robots, while Her (2013) features a lonely writer who falls in love with the Siri-like virtual assistant on his mobile phone operating system. Both raise weighty ethical questions about the nature of consciousness and the potential dangers of AI.

And let’s not forget The Matrix (1999), where the humanity of the future is trapped in a simulated reality created by advanced AI systems. Only a small band of humans (led, of course, by Keanu Reeves) can rebel against their machine overlords and fight for their freedom.

All of these plotlines can be traced back to 1968, and Stanley Kubrick’s astonishingly influential 2001: A Space Odyssey. This was the first mainstream film to seriously tackle the risks that AI poses regarding transparency and accountability in AI decision-making.

Kubrick always had a deep interest in AI, and told an interviewer in 1969 that one of the things he was trying to convey in 2001 was the reality of a world soon to be populated by machines like the super-computer HAL “who have as much, or more, intelligence as human beings, and who have the same emotional potentialities in their personalities as human beings”.

Kubrick, like James Cameron and the Wachowski sisters would do in The Terminator and The Matrix, frames 2001 as a cautionary tale. He and co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke (himself an early proponent of the benefits of AI) explore the boundaries and consequences of human interaction with intelligent machines and suggest that machines have the unfailing capacity to evolve beyond their programmed intentions and develop their own motivations and actions.

HAL’s subsequent malfunction in 2001 and its subsequent attempts to eliminate the human crew highlight the potential threats and ethical considerations associated with the development of advanced AI. And Hollywood has run with this idea ever since, starting with HAL’s large red ‘eye’ as the personification of the ‘bad robot’.

AI has been widely embraced by the film industry in other ways, which loops us right back to the current strike action in Hollywood.

“Digital de-ageing” first entered the mainstream in 2019 with The Irishman and Captain Marvel. Via this process, older actors (Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Samuel L. Jackson) moved back and forwards in time without younger actors having to play them.

The first part of this year’s Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny is an extended flashback, set in 1944, in which Harrison Ford was digitally de-aged to appear thirty years younger. By deploying an AI system that scanned unused reels of footage of Ford from his Indiana Jones incarnations of the 1980s to match his present-day performance, audiences got two Fords for the price of one; the “younger”, fitter Indy, and the older, world-wearier version.

These de-ageing algorithms are highly proficient at analysing vast amounts of data, including images and videos, to learn patterns and features associated with different age groups.

By scrutinising facial structures, wrinkles, and other ageing characteristics, these AI tools can generate realistic representations of a person at a younger age. It makes for a powerfully emotional connection on screen, but there are pitfalls. Some viewers complain that the whole process is distracting and that the hyper-real visual look of de-aged scenes resembles a video game.

Even so, de-ageing in Hollywood cinema is here to stay. Tom Hanks’s next film will use AI-based generative technology to digitally de-age him. In the midst of the current industry uncertainty, it seems there is no longer a statute of limitations on actors returning to much-loved characters.

The next big ethical issue for the film industry as it further embraces AI is whether to resurrect deceased actors and cast them in new movies. Some directors already are imagining hooking up AI to streaming platforms to create “new” films in which we become the stars, interacting with long-dead actors.

In a recent interview, Steven Spielberg warned: “The human soul is unimaginable and ineffable. It cannot be created by any algorithm. This is something that exists only in us. If we were to lose that because books, films, music tracks are being created by the machines we have made? Are we going to let all this happen? It terrifies me.”

When the director of two intricately woven films – Minority Report (2002) and AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001) – that ask unsettling questions about how synthetic humans and computer systems might interact with us in a not-too-distant future reminds us to be careful what we wish for, perhaps we should listen.

Film is reaching a pivotal point in its relationship with AI. In Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), the mad scientist Rotwang created a robot replica of Maria (hitherto a virtuous woman who becomes a symbol of hope for the city’s oppressed workers) to sow discord and chaos.

This new ‘false’ Maria is one of cinema’s most enduring ‘bad robots’: in the film, she becomes a seductive and manipulative figure who almost leads to the city’s destruction. A century later, those fears and anxieties about the rise of the machines are still with us.

Story by Dr Ben McCann SFHEA, Associate Professor of French Studies – and an avid film scholar and writer.