I made bushfire maps from satellite data, and found a glaring gap in Australia’s preparedness

Image courtesy of Greg Harvie, Author provided

On the night of January 9 2020, my wife and I secured our Kangaroo Island home and anxiously monitored the South Australian Country Fire Service (CFS) website for bushfire advice.

After many horrific weeks of bushfires, the winds had again shifted, and the fire front began a slow, nightmarish march eastward into the island’s central farmlands. Official warnings advised that the entire island was potentially under threat.

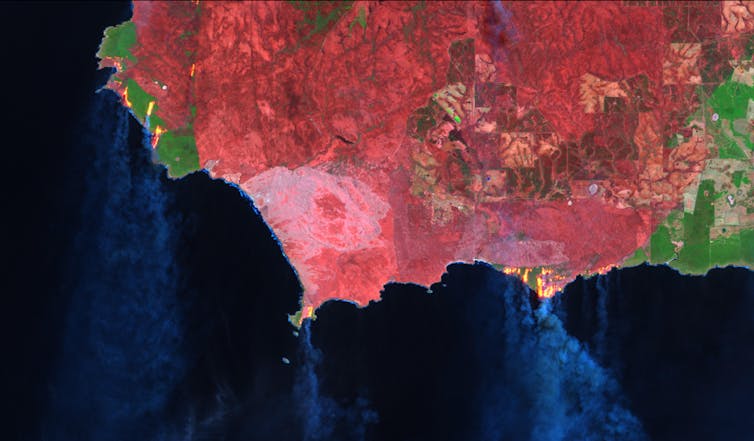

Landsat-8 false colour image of southwest Kangaroo Island, showing active bushfires on January 9, 2020. Landsat-8, Author provided

As my good neighbours and volunteer firefighters headed off to battle the flames elsewhere on the island, I desperately wanted to find a way to help. With no firefighting training, I felt I physically had little to offer. But I reasoned that my skills and training in remote sensing and spatial science could potentially turn satellite information into useful maps to track the fires, in more detail than those provided by the Country Fire Service and Geoscience Australia.

While I was ultimately successful, it wasn’t quite as straightforward as I thought. And what I learned about access to good-quality and up-to-date satellite bushfire information surprised me.

Free satellite imagery is abundant; useful information is not

In principle, there are many good sources of free satellite imagery. But selecting, sourcing, understanding and processing a multilayered satellite image into an accurate burnt area map takes technical know-how that is beyond the reach of the people who need it the most.

We are fortunate to live in a time where satellite images are constantly uploaded to the web, often within hours of acquisition. There are many reputable sources for this information, including NASA Worldview, USGS Earth Explorer, USGS LandLook Viewer, and the Sentinel EO Browser.

These websites are gateways to the world of “big satellite data”, and I quickly found myself on a steep learning curve to efficiently navigate them and find recent imagery.

Once downloaded, the next hurdle I faced was how to process a data-rich satellite image into a meaningful and accurate map of the bushfire area. I scoured the internet for “how to” blogs, academic articles, spatial algorithms, and processing codes; these too are the products of much intellectual investment by global scientists, openly and freely available.

As a spatial scientist, I naturally found all this fascinating. But as a resident of an island under assault from bushfires, I also found it frustratingly time-consuming. I crashed my computer testing algorithms. I maxed out my hard drive. I spent hours on possibilities that turned out to be dead ends.

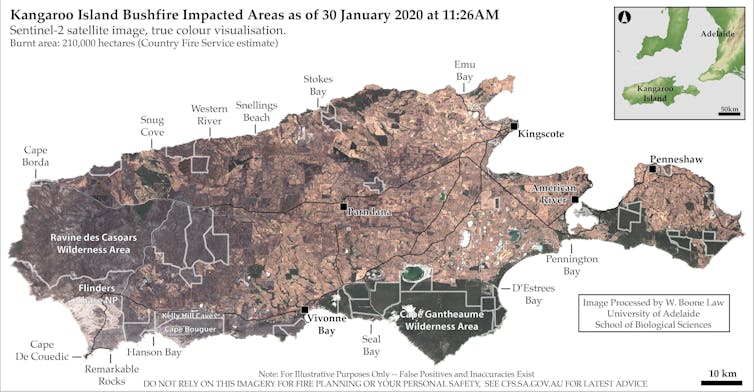

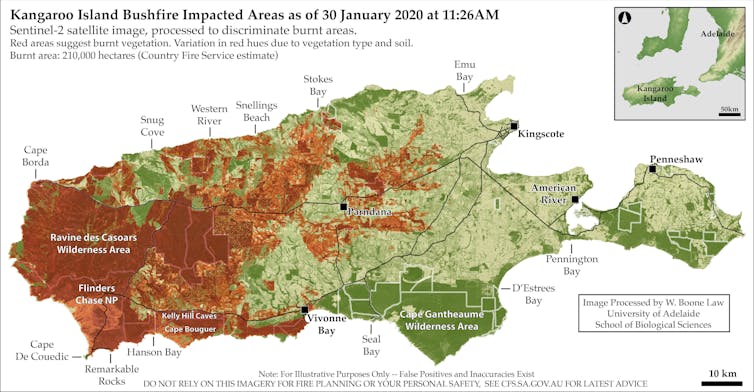

True colour satellite imagery is often the most accessible and easily understood, but it often lacks sufficient detail to clearly identify burnt areas. In this Sentinel-2 true colour image, approximately 210,000 hectares are burnt, but bushfire-impacted areas are barely visible without advanced image processing. Sentinel-2, Author provided

Maps help to fight fires and recover from them

In the end, I produced burnt area maps from Sentinel and Landsat satellite images captured during the fires. I learned that this kind of information can indeed help firefighting and ecological recovery efforts, both during and after bushfires.

Initially I gave the maps to a group of farming friends who had been fighting fires around their properties for weeks. They told me the maps helped save time in assessing which areas had already burned, allowing them to focus on defending unburnt areas, and to make decisions on where to move livestock and install firebreaks.

The positive feedback inspired me to customise my processing techniques, so I could provide updates more quickly when new satellite images became available.

I embedded appropriate safety disclaimers into the maps and released them on Twitter and Spatial Points, a blog site managed by my research group at the University of Adelaide.

Within hours, I received messages that the maps were being used for ecological recovery efforts. The maps successfully highlighted remaining patches of habitat where endangered and vulnerable species had found refuge. Several government agencies even contacted me for burnt area information, which I’m told was used to assess infrastructure damage and habitat loss.

Processed Sentinel-2 satellite image. Red areas suggest burnt vegetation. Variation in red hues are caused by dominant vegetation type and soils. Sentinel-2/W. Boone Law, Author provided

National knowledge gap

My experience shows there is a swag of free and regularly updated satellite imagery available, which when interpreted and presented appropriately can potentially be hugely helpful to firefighting and recovery efforts.

However, I am concerned that neither the general public nor decision-makers seem fully aware of the range of satellite information on offer. Nor is there a good understanding of the advanced technical skills needed to access and process imagery into useful map data.

Read more: Yes, the Australian bush is recovering from bushfires – but it may never be the same

This leads me to wonder whether I have stumbled upon a glaring knowledge gap in Australia’s bushfire preparedness.

How can we overcome this technological and information bottleneck? I don’t propose to have all the answers, but I do believe it would be sensible for governments, industry and research agencies to invest in the kind of capabilities that I developed while trying to protect my own local community.

As Australia faces a future of more frequent and extreme bushfires, there will doubtless be many people who would be glad of this kind of information when they need it most. ![]()

Featured researcher

Mr Wallace Law

PhD Candidate

School of Biological Sciences

Faculty of Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wallace Boone Law, PhD Candidate, University of Adelaide