As climate change worsens Adelaide will become a 50 degree city

Climate change means Adelaide is already on a path towards unavoidable destruction. But if we act now, we can avoid the worst, says environmental expert Robert Hill.

Professor Robert Hill doesn’t paint a pretty picture. But then again, he doesn’t want to. Too much time has already been wasted – and the time for patience and gentle persuasion has passed. Sitting in his University of Adelaide office, overlooking the Barr Smith lawns, Hill is talking about the dangers of climate change, not only to the globe but to South Australia in particular.

There are two aspects, as he sees it. There is the stuff that it’s too late to do anything about. For example, rising sea levels will mean Adelaide coastal suburbs such as Grange will be underwater by the end of the century. But Hill, director of the university’s Environment Institute, also says there is still time to avoid the worst. That if we take steps to reign in rising temperatures then Adelaide may still be a liveable city by the end of the century. If we don’t – and he says targets such as net zero carbon emissions by 2050 are much too slow and much too late –then we are going to be in a world of trouble. “If we don’t, the alternative is hard to imagine,’’ Hill says. “But you are talking Mad Max territory is where it’s likely to end up if we don’t do this.’’

Mad Max being the Mel Gibson film set in a post-apocalyptic, dystopian future where battles are fought for water and fuel. Hill stresses he is not trying to be alarmist. But he’s looked at the science, looked at the data and is frightened that this is a disaster that we are not doing enough to prevent. He points to the numbers of extreme heat days South Australia has experienced in the past decade as just one measure that is concerning. Research shows that for much of the past century there would be about six days above 42C per decade. Of course, Australia has always been a hot country. The point is, now we are seeing it heat up as we never seen before.

“Twenty years ago it went up to about up to about 20 (days a decade). Last decade it was nearly 50. We have gone from five or six to 50. That’s a line going straight up, so where does the next decade go?’’ Adelaide recorded its highest temperature of 46.6C in 2019. In December that year, three consecutive days above 45C were recorded. On December 20 at Roseworthy, north of Adelaide, a temperature of 47C was posted. The same day the Cudlee Creek bushfires started, destroying more than 70 homes. The next month fires raged through Kangaroo Island. At the same time, great swathes of Victoria and New South Wales were also ablaze. Such fire storms are predicted to become more regular as Australia continues to heat up.

Hill believes we are on the way to becoming a 50C city. It’s a point at which Adelaide will become essentially unliveable. “I don’t want to be too dramatic, but if you don’t consider that option you have your head in the sand. If we don’t do something that is the risk we face,’’ he says. “There are not many places in Australia that are genuinely worried about that (getting to 50C) yet, but I think we are and I think parts of Sydney are. It’s a matter of who gets there first. “Not whether, but when.’’ Hill acknowledges that in a global sense it’s hard for South Australians on their own to do much about lowering global temperatures. But he also says there are actions we can take to keep Adelaide a place where people still want to live.

[caption id="attachment_15686" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Image: By Annemarie Gaskin, Climate Strike 2019[/caption]

Image: By Annemarie Gaskin, Climate Strike 2019[/caption]He says increasing tree cover is vital. Not all of Adelaide will become a 50 degree city at once. It’s likely to hit the city’s northern suburbs, where there are fewer trees, first. “It doesn’t matter what the rest of the planet does, we can do something about it here, so we should be focusing on the issues where we can make a difference.’’ A recent report endorsed by the Conservation Council of SA the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, National Trust SA and Trees for Life estimated that Adelaide is losing 75,000 trees a year, a figure which adds up to an area double the size of the city’s CBD every decade. The report said changes to laws in 2011 made it too easy for large trees to be removed.

Releasing the report, Council chief executive Craig Wilkins said: “If this continues we have zero chance to meet the state government target of increasing urban green cover by 20 per cent in metro Adelaide by 2045.’’ Last year, the mayors of 11 metropolitan councils wrote to Planning Minister Vickie Chapman warning that Adelaide was losing mature trees at an “alarming rate’’ and that the deficit could not be made up by planting new trees. Many trees are being lost as traditional quarter acre blocks, with family homes, are cleared and existing trees removed. They are being replaced by high-density housing with small, treeless, garden areas. It’s a problem only likely to grow, with a report released last week claiming Adelaide will need a further 88,000 homes over the next decade as its accommodates an extra 220,000 people.

The state government land supply report says there are 168,624 blocks suitable for development in existing neighbourhoods. It also says housing density has increased from 10 lots a hectare in 2010 to 12.3 in 2019 and that an average of 2000 homes a year are demolished in Adelaide. In the letter, the mayors say there is not enough space on public land to replace trees lost on private property, that even if you do replace a mature tree with several young trees there will still be a loss of canopy and that climate change makes it more difficult for young trees to establish themselves. Hill says we are not just losing trees because of development decisions but also because of the increasing numbers of extreme heat days.

“You don’t need that many days of that really extreme heat and you start killing trees, you start effecting human health,’’ he says. “Trees and plants really matter to a city. They keep it liveable for all sorts of reasons, including shade and water. “If you start taking those trees out you are in really bad shape and we are doing that. It’s not just trees dying from heat, when a tree dies from heat it’s really dying from a lack of water. There are trees all over Adelaide that appear to be dying or dead probably as a result of that.’’ Hill says while the sheer number of extreme heat days have brought the problem of climate change back into public focus, part of the reason we are still not taking the problem seriously enough is that we have become gradually used to hotter summers. It’s the fable of the frog in the boiling water. If you throw a frog in a pot of boiling water it will jump straight out, but if you put it in cold water and slowly increase the heat it stays there and is boiled alive.

In Hill’s terms “people change their baselines very quickly’’. So, instead of comparing recent hot summers to those of 20 or 30 years ago, there is a tendency to compare them to only five or six years ago. The problem with that kind of recency bias is that the summers of five or six years ago were already far hotter than they should have been. South Australia’s most recent summer was generally regarded as being relatively mild, butHill says that is only the case, if you compared to it to our most recent summers. “I have been around a long time now and I can remember summers that were a lot colder than the last summer,’’ he says. “We have to be really careful about what we are comparing to in our own experience of life. That’s proving to be quite dangerous.’’ But it’s not all doom and gloom. Hill says it’s not too late to do something about it, but the federal government needs to stop avoiding the problem and take serious action. Hill doesn’t consider a 2050 target to move Australia to net zero emissions, which the government has still not committed to, as a serious target. “We should be aiming for a lot faster than that. That’s definitely too slow. How quickly? As quickly as we can,’’ he says.

[caption id="attachment_15683" align="alignnone" width="716"]

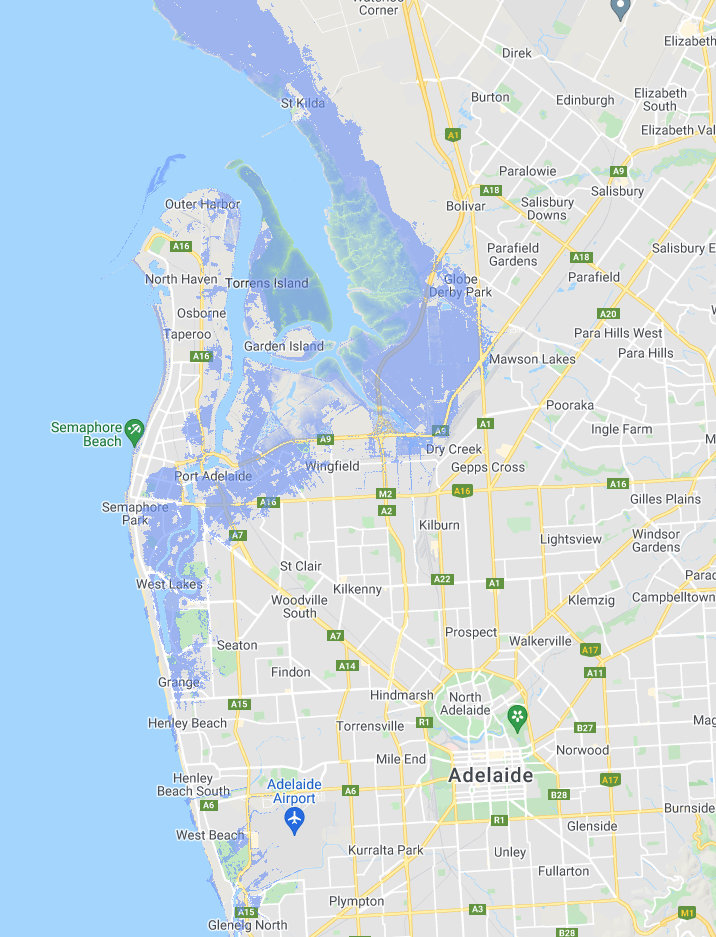

Image: by Coastal Risk. Shows parts of Adelaide under water by 2100.[/caption]

Image: by Coastal Risk. Shows parts of Adelaide under water by 2100.[/caption]Hill believes it’s possible the world will come together and solve this problem. He takes some comfort from some of the global unity in fighting the Covid-19 virus and is hopeful world leaders can work together to fight climate change.

“We didn’t to do badly at that (Covid) but we will have to do better at climate change. And it’s going to be harder,’’ he says. The difference between climate change and Covid responses is that people felt an immediate threat because of the pandemic. They thought they could die. “That focuses your mind. Climate change isn’t like that. It’s not quite so immediate, so it’s much more difficult to get people to focus on a problem that is not so immediately impacting on them.’’ New technologies will also be part of the solution. Hill references a process called direct air capture (DAC) as potential solution with promise. Essentially this is a machine that sucks carbon dioxide out of the air. Reducing the planet’s carbon emissions is a key plank in the goal to limit global warming to below 2C from pre-industrial levels. This can be done by passing air over a special liquid and the carbon dioxide sticks to the mixture. The captured carbon dioxide can then be used to manufacture plastic or even fuel. A Swiss company called Climeworks is planning to convert the carbon dioxide to jet fuel at Rotterdam airport in the Netherlands. The CSIRO is also developing DAC technology here. “If we don’t get big technological solutions to this, it won’t happen. It’s too late for anything else,’’ he says. “You go about it that way, we might just be clever enough to save it (the planet).’’

Of course, what Hill is talking about is saving humanity, rather than the planet itself. The planet will be here long after we are gone. “We can’t do anything that will irreversibly damage the earth,’’ he says. “There have been far worse things that have happened in the past and it has recovered. But we can make it so that it is irreversibly damaged for us.’’ Rising sea levels could consume cities such as Shanghai, Mumbai and Bangkok, In Australia, the Bureau of Meteorology website shows predicted flooding levels by 2100 by council area.

Under its “very high greenhouse gases” scenario, suburbs such as West Lakes, Semaphore South, Glanville, Port Adelaide, Largs Bay and Peterhead could all be under water. Hills says the amount of ice held in places such as Greenland and Antarctica would overwhelm the planet if it melted. He is not forecasting this will happen but says if all the ice in Antarctica melted, sea levels would rise 70m. The new level would have water lapping over the Sydney Harbour Bridge. “There are ice sheets several kilometres thick over most of Antarctica.’’ Hill says future generations are going to look back at us and wonder why more was not done quicker. He says they will look at us, the same we look at the Germany of the 1930s that allowed the Nazis to take power.

“I have grandchildren. I think history will judge my generation and the one before it very poorly. “People 20, 30, 40 years from now will look back and say “how were they so ignorant that they let the situation degenerate to that point?’.

Original story by Michael McGuire, published in SA Weekend

Professor Hill and the Environment Institute has a team ready respond to climate change in Adelaide called Green Urban Futures

Newsletter & social media

Join us for a sensational mix of news, events and research at the Environment Institute. Find out about new initiatives and share with your friends what's happening.