The pursuit eternal

Pioneering research in plant breeding, alternative proteins, and transformative technologies keeps the Waite at the cutting edge in its constant pursuit of the next big thing.

At the core of the Waite’s research is innovation and a commitment to sustainability.

Researchers at the Waite are currently working on projects such as insect proteins; plants like hemp and duckweed, which have novel industrial and space-faring applications; hops, a crop with a developing local market; reducing chemical residues of herbicides and chemical sprays; and no-and-low-alcohol (NOLO) wines.

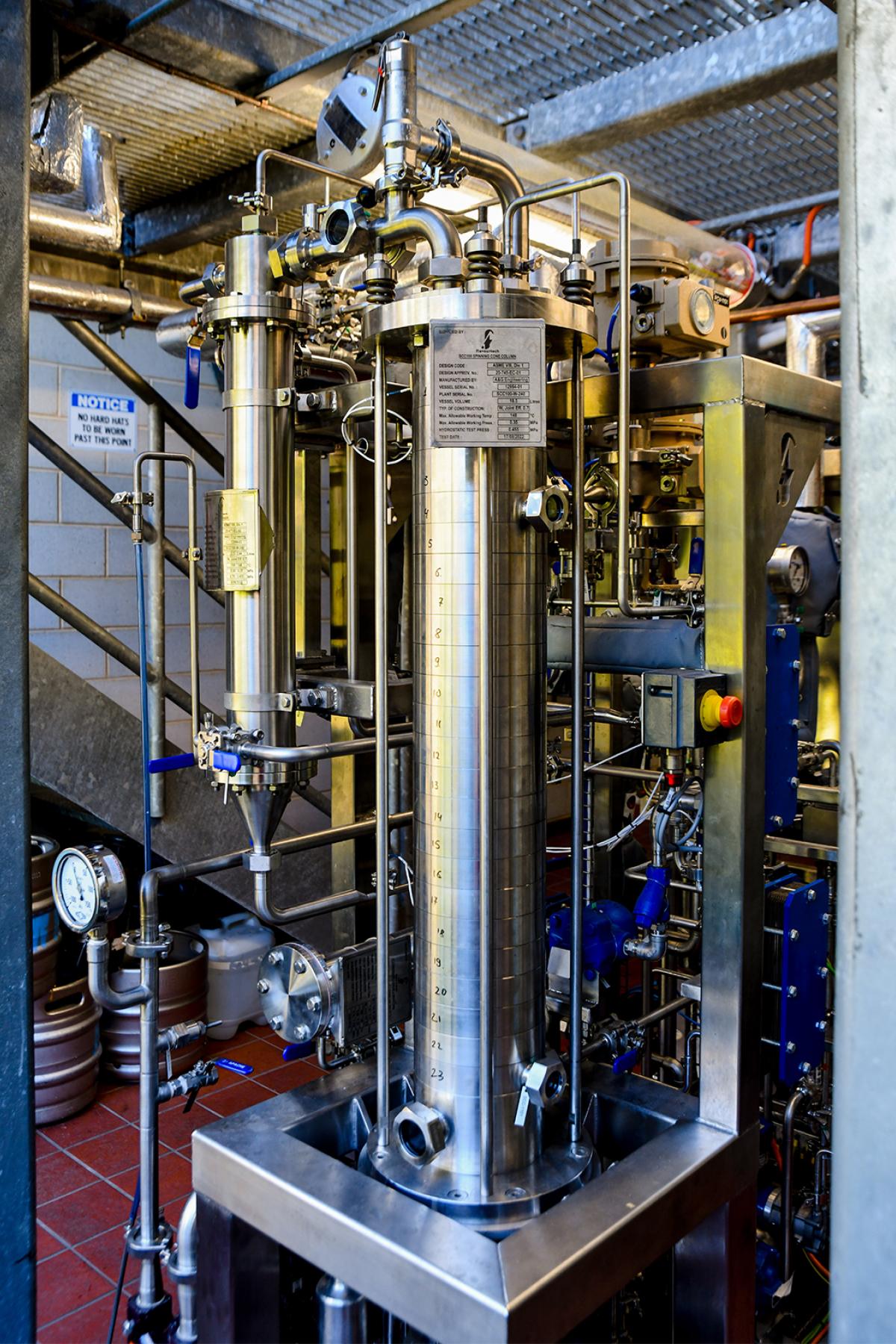

Associate Professor Paul Grbin, Head Winemaker and co-lead of the Wine Microbiology Group in the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine’s Department of Wine Science, is one of the researchers leading the venture set to reshape winemaking. Funded by the South Australian government through the Department of Primary Industries and Regions in South Australia (PIRSA), the NOLO project boasts an investment of $1.98 million and partners with the Australian Wine Research Institute.

The facility allows for the development of NOLO research and product development and assists wineries in creating innovative products, guiding them through the entire process – from conception to packaging – without significant upfront costs.

“Our main technology for removing alcohol is something called a spinning cone, and this allows small and medium wineries to come and try to develop a product they don’t yet know will work with small financial inputs,” Paul says.

This project is unique in the context of Waite’s research focus. Where most market-related work is done by the business school, for the NOLO team, it also focuses on consumer research from a sensory point of view, with research also going into understanding what consumers want in terms of taste and feel.

“The challenge is to produce a no-or-low-alcohol product that provides a wine-like experience without the downsides of alcohol,” Paul says.

Unlike other research areas at the Waite, the NOLO project symbolises the possibilities and strength of the teams working at the campus and sets an example for research that converges scientific expertise, industry collaboration, and market research, aiming to shape a new era in winemaking. Professor Jason Able, Head of the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, says the work being done at the Waite is vital to the future prosperity and sustainability of our time on Earth.

“We’re now looking at the next wave, or the next generation of crops and commodities for breeding programs. They’re not mainstream like those crops that have come before us in the last hundred years,” Jason says. “When you think about climate change, then we’ve got to start thinking about building resilience to this ever-changing climate. We can start to think about resilience in environments where commodities are not typically grown.”

The University’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of conventional agriculture opens the door to more opportunities and a more sustainable future for growers.

“Due to climate change and an ever-changing environment, part of a breeder’s remit will definitely be to try their most advanced germplasm in very challenging environments,” Jason says. “Breeders will start considering future-proofing for that particular area or region where a grower might need it for things like yield improvement, disease resistance, water use efficiency, nutrient deficiencies.”

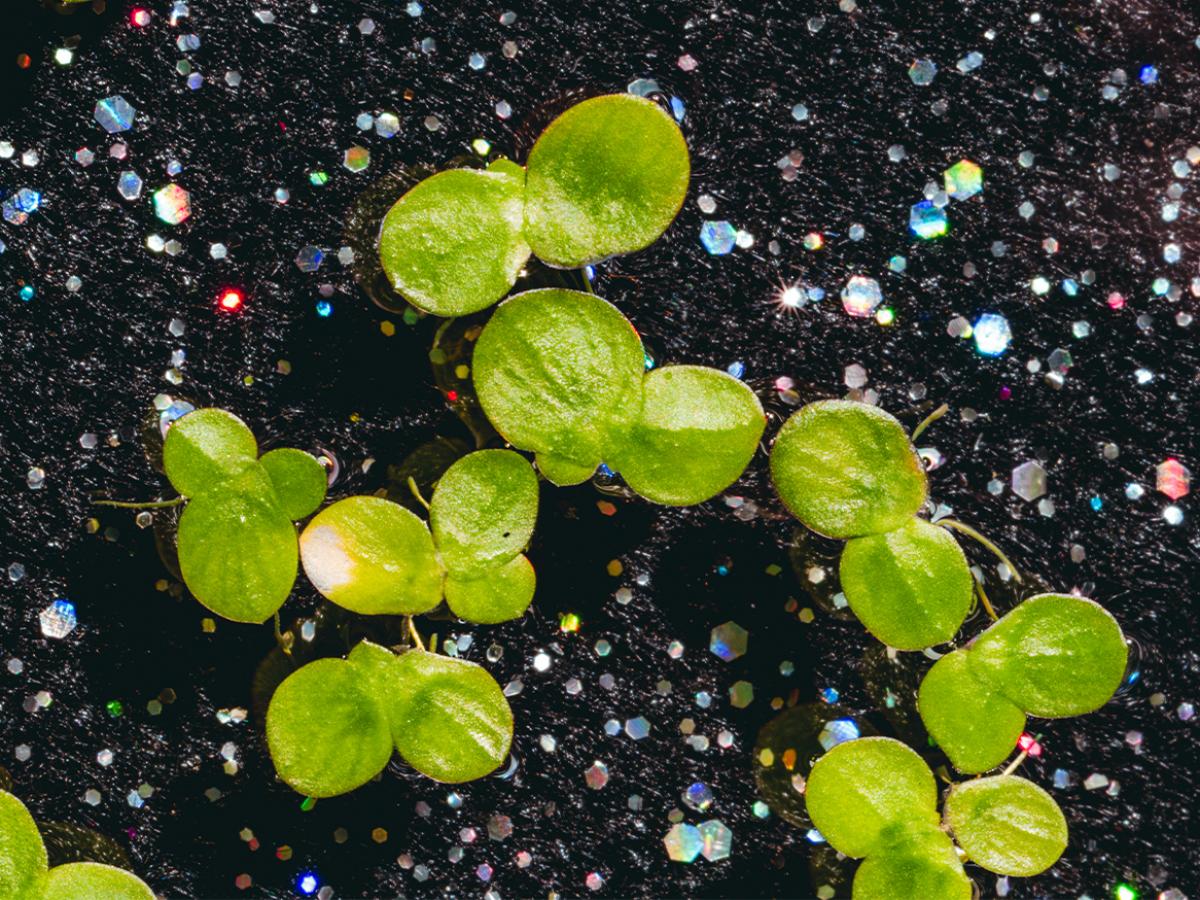

The unassuming yet powerful duckweed is one plant being tested for a very challenging environment, and stands as a potential game-changer for sustainable agriculture and a revolutionary protein source. Associate Professor of Plant Synthetic Biology in the School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, Jenny Mortimer, is leading the research that focuses on engineering crops for future challenges.

“My research isn’t just using food crops. It’s actually developing new dedicated crops, especially for the production of biofuels and biomaterials,” Jenny says. “In addition to that, as climate change becomes more of an issue alongside growing populations, we explore how we can engineer the crops of the future.”

With concerns of reductions in space, Jenny focuses on the need for rapidly growing plants in indoor and vertical farming, where plants like duckweed take centre stage. This is something Jenny believes scientists need to consider quickly as the world rapidly changes. In battling the space and time investment required for current crops, Jenny applies civil engineering principles to biological systems.

This is synthetic biology, which seeks to streamline the process of creating genetic blueprints for desired compounds. However, the conventional growth pace of plants, particularly field crops, poses a significant challenge to this method. “If your plant takes four or five months to go from seed to seed, it takes you forever,” Jenny says.

Duckweed became a logical focal point for its small size and entirely edible composition, and because it is capable of continuous growth, high protein production, and is adaptable to indoor environments. Beyond growth speed, duckweed’s rich composition of essential amino acids makes it a potent protein source, allowing for continuous growth and up to 60 times more protein production compared to traditional crops like soybean. Jenny says this makes it a suitable consideration for space exploration.

The challenge of sustaining humans on a trip to Mars prompts the exploration of growing plants in space. With weight limitations and addressing nutrient degradation and monotony of packaged food, alternatives become critical. Jenny encourages students to look to the environment in space as the ultimate experience in food sustainability, which can help prompt vital innovations.

“The challenge is to produce a no-or-low-alcohol product that provides a wine like experience without the downsides of alcohol" Associate Professor Paul Gribin

“You can’t take all the food you would need to carry with you on a trip to Mars. For a nine-month return trip for four people, you’d need something like 10 tonnes of food,” she says. “But also, they get bored of the brown sludgy meals they end up eating, and the nutrients degrade over time and so the astronauts would start to lose weight. So there’s a lot of interest in trying to grow plants as you go.

“Space is the ultimate in sustainability when you’re thinking about producing things; you can only use the resources you have there and you have to recycle everything because you can’t get more of anything. And that’s a really good way of thinking about the on-Earth applications, because it really inspires you to problem solve for sustainability in the space context. And we can use that learning to help us inform what’s possible on Earth.”

For a tiny plant, the research into duckweed and other plants just like it proves that with a little innovation and focus on sustainability, the next game-changer could be hiding within the labs at Waite.

Written by Anna Kantilaftas

Photography by Jack Fenby