Subcutaneous Mycoses

These are chronic, localized infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue following the traumatic implantation of the aetiologic agent.

The causative fungi are all soil saprophytes of regional epidemiology whose ability to adapt to the tissue environment and elicit disease is extremely variable.

| Disease | Causative organisms | Incidence |

|---|---|---|

| Sporotrichosis | Sporothrix spp. | Rare |

| Chromoblastomycosis | Fonsecaea, Phialophora, Cladophialophora etc. |

Rare |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | Cladophialophora, Exophiala, Curvularia, Exserohilum etc |

Rare |

| Mycotic mycetoma | Scedosporium, Madurella, Trematosphaeria, Acremonium, Exophiala etc. |

Rare |

| Subcutaneous zygomycosis (Entomophthoromycosis) |

Basidiobolus ranarum Conidiobolus coronatus |

Rare |

| Subcutaneous zygomycosis (Mucormycosis) |

Rhizopus, Mucor, Rhizomucor, Lichtheimia, Saksenaea etc. |

Rare |

| Lobomycosis | Loboa loboi | Rare |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Rhinosporidium seeberi | Rare |

Mycoses descriptions

-

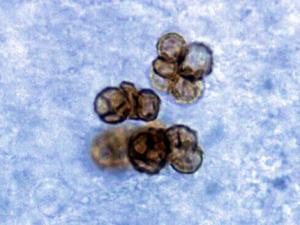

Chromoblastomycosis

A mycotic infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues characterised by the development in tissue of dematiaceous (brown-pigmented), planate-dividing, rounded sclerotic bodies. Infections are caused by the traumatic implantation of fungal elements into the skin and are chronic, slowly progressive and localised. Tissue proliferation usually occurs around the area of inoculation producing crusted, verrucose, wart-like lesions. World-wide distribution but more common in bare footed populations living in tropical regions. Aetiological agents include various dematiaceous hyphomycetes associated with decaying vegetation or soil, especially Phialophora verrucosa, Fonsecaea spp., and Cladophialophora carrionii.

Clinical manifestations:

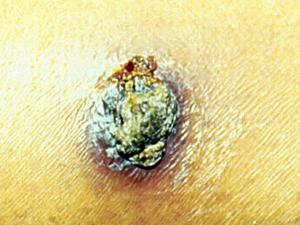

Lesions of chromoblastomycosis are most often found on exposed parts of the body and usually start a small scaly papules or nodules which are painless but may be itchy. Satellite lesions may gradually arise and as the disease develops rash-like areas enlarge and become raised irregular plaques that are often scaly or verrucose. In long standing infections, lesions may become tumorous and even cauliflower-like in appearance. Other prominent features include epithelial hyperplasia, fibrosis and microabscess formation in the epidermis. Chromoblastomycosis must be distinguished from other cutaneous fungal infections such as blastomycosis, lobomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis and sporotrichosis. It may also mimic protothecosis, leishmaniasis, verrucose tuberculosis, certain leprous lesions and syphilis. Mycological and histopathological investigations are essential to confirm the diagnosis.

Click images below to expand:

Note: tissue hyperplasia forming a white verrucoid cutaneous lesion. In Australia, chromoblastomycosis due to C. carrionii occurs mostly on the hands and arms of timber and cattle workers in humid tropical forests.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Skin scrapings and/or biopsy.Direct microscopy:

(a) Skin scrapings should be examined using 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts; (b) Tissue sections should be stained using H&E, PAS digest, and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS).Interpretation:

The presence in tissue of brown pigmented, planate-dividing, rounded sclerotic bodies from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Remember direct microscopy or histopathology does not offer a specific identification of the causative agent. Note: direct microscopy of tissue is necessary to differentiate between chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis where the tissue morphology of the causative organism is mycelial.Click images below to expand:

Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar.Interpretation:

The dematiaceous hyphomycetes involved are well recognised as environmental fungi, therefore a positive culture from a non-sterile specimen, such as sputum or skin, needs to be supported by clinical history and direct microscopic evidence in order to be considered significant. Culture identification is the only reliable means of distinguishing these fungi.Serology:

There are currently no commercially available serological procedures for the diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis.Identification:

Culture characteristics and microscopic morphology are important, especially conidial morphology, the arrangement of conidia on the conidiogenous cell and the morphology of the conidiogenous cell. Cellotape flag and/or slide culture preparations are recommended.Causative agents:

Cladophialophora carrionii, Fonsecaea species complex, Phialophora verrucosaFurther reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Esterre P, Inzan CK, Ramarcel ER, Andriantsimahavandy A, Ratsioharana M, Pecarrere JL, Roig R, Treatment of chromomycosis with terbinafine: preliminary results of an open pilot study. Br J Dermatol (1996) 134 (Suppl. 46):33-36.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co. -

Lobomycosis

Lobomycosis is a chronic, localised, subepidermal infection characterised by the presence of keloidal, verrucoid, nodular lesions or sometimes by vegetating crusty plaques and tumours. The lesions contain masses of spheroidal, yeast-like cells of Lacazia loboi. There is no systemic spread. The disease has been found in humans and dolphins and is restricted to the Amazon Valley in Brasil.

Clinical manifestations:

Lobomycosis showing extensive verrucoid lesions on the legs

(Courtesy of John Rippon, USA).The initial infection is thought to be caused by traumatic implantation such as an arthropod sting, snake bite, sting-ray sting, or wound acquired while cutting vegetation. The lesions begin as small, hard nodules resembling keloids and may spread slowly in the dermis and continue to develop over a period of many years. Older lesions become verrucoid and may ulcerate. The disease may be transfered to other areas of of the skin by further trauma or autoinoculation. Thus the areas of involvement may become quite extensive. Lesions are usually found on the arms, legs, face or ears.

90% of cases are men, mostly in farmers and other high risk groups exposed to various harsh conditions as well as aquatic habitats.

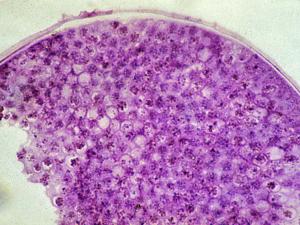

GMS stained tissue specimen showing numerous darkly pigmented yeast-like cells, often in chains, 9-12 um in size.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Tissue sample obtained by curettage or surgical biopsy.Direct microscopy:

(a) Tissue can be macerated and mounted in 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts or (b) Tissue sections should be stained using PAS digest, Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) or Gram stains.Interpretation:

The presence of chains of darkly pigmented, spheroidal, yeast-like organisms tentatively referred to as Loboa loboi is typical for lobomycosis.Culture:

The aetiologic agent known as Lacazia loboi remains to be cultured.Serology:

There are currently no serological tests available.Identification:

Clinical features, geographic location and microscopic morphology are important.Causative agents:

Lacazia loboiFurther reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co. -

Mycetoma

A mycotic infection of humans and animals caused by a number of different fungi and actinomycetes characterized by draining sinuses, granules and tumefaction. The disease results from the traumatic implantation of the aetiologic agent and usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue, fascia and bone of the foot or hand. Sinuses discharge serosanguinous fluid containing the granules which vary in size, colour and degree of hardness, depending on the aetiologic species, and are the hallmark of mycetoma. World-wide distribution but most common in bare-footed populations living in tropical or subtropical regions. Aetiological agents include Madurella, Acremonium, Scedosporium, Exophiala, Leptosphaeria, Curvularia, Fusarium, Aspergillus etc.

Mycetoma showing numerous draining sinuses. There is destruction of bone, distortion of the foot, and hyperplasia at the openings of the sinus tracts. (Courtesy John Rippon USA).

Mycetoma is a chronic, suppurative infection of the subcutaneous tissue and contiguous bone. The clinical features are fairly uniform, regardless of the organism involved. The feet are the most coomon site for infection and account for at least two-thirds of cases. Other sites include the lower legs, hands, head, neck, chest, shoulder and arms. Most cases start out as a small hard painless nodule which over time begins to soften on the surface and ulcerate to discharge a viscous, purulent fluid containing grains. The infection slowly spreads to adjacent tissue, including bone, often causing considerable deformity. Sinuses continue to discharge serosanguinous fluid containing the granules which vary in size, colour and degree of hardness, depending on the aetiologic species. These grains are the hallmark of mycetoma.

Excised mycetoma showing a draining sinus (cut open in this preparation) containing black grains

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Tissue biopsy or excised sinus, serosanguinous fluid containing the granules which vary in size, colour and degree of hardness, depending on the aetiologic species.Direct microscopy:

Serosanguinous fluid containing the granules should be examined using either 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts, and tissue sections should be stained using H&E, PAS digest, and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS).

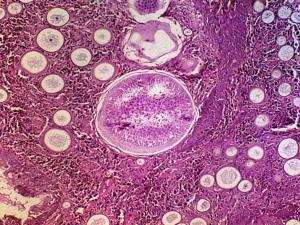

H&E stained tissue section showing blacked grained eumycotic mycetoma caused by Madurella mycetomatis.

Interpretation:

The presence of white to yellow or black pigmented grains, from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Biopsy and evidence of tissue invasion is of particular importance. Remember direct microscopy or histopathology does not offer a specific identification of the causative agent.Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar.Serology:

There are currently no commercially available serological procedures for the diagnosis of mycetoma.Identification:

Characteristic clinical, microscopic and culture features.Causative agents:

Acremonium sp., Aspergillus nidulans, Trematosphaeria grisea, Madurella mycetomatis, Scedosporium apiospermum.Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co. -

Phaeohyphomycosis

A mycotic infection of humans and lower animals caused by a number of dematiaceous (brown-pigmented) fungi where the tissue morphology of the causative organism is mycelial. This separates it from other clinical types of disease involving brown-pigmented fungi where the tissue morphology of the organism is a grain (mycotic mycetoma) or sclerotic body (chromoblastomycosis). The etiological agents include various dematiaceous hyphomycetes especially species of Exophiala, Phialophora, Exserohilum, Cladophialophora, Verruconis, Aureobasidium, Cladosporium, Curvularia and Alternaria. Ajello (1986) listed 71 species from 39 genera as causative agents of phaeohyphomycosis.

Clinical manifestations:

Clinical forms of phaeohyphomycosis range from localized superficial infections of the stratum corneum (tinea nigra) to subcutaneous cysts (phaeomycotic cyst) to invasion of the brain.

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis:

Subcutaneous infections occur worldwide, usually following the traumatic implantation of fungal elements from contaminated soil, thorns or wood splinters. Exophiala jeanselmei and Wangiella dermatitidis are the most common agents and cystic lesions occur most often in adults. Occasionally, overlying verrucous lesions are formed, especially in the immunosuppressed patient.Click images below to expand:

Paranasal sinus phaeohyphomycosis:

Sinusitis caused by dematiaceous fungi, especially species of Exserohilum, Curvularia and Alternaria is increasingly being reported, especially in patients with a history of allergic rhinitis or immunosuppression.Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis:

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis is a rare infection, occurring mostly in immunosuppressed patients following the inhalation of conidia. However, cerebral infections caused by Cladophialophora bantiana have been reported in a number of patients without any obvious predisposing factors. This fungus is neurotropic and dissemination to sites other than the CNS is rare.Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Skin scrapings and/or biopsy; sputum and bronchial washings; cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid and blood; tissue biopsies from various visceral organs and indwelling catheter tips.

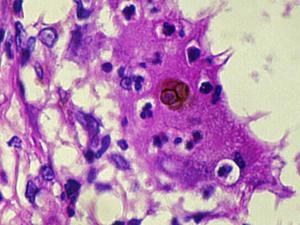

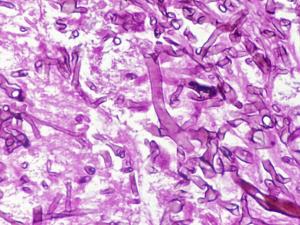

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section showing characteristic, brown-pigmented, septate hyphal elements of Exophiala jeanselmei.

Direct microscopy:

(a) Skin scrapings, sputum, bronchial washings and aspirates should be examined using 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts; (b) Exudates and body fluids should be centrifuged and the sediment examined using either 10% KOH and Parker ink or calcofluor white mounts, (c) Tissue sections should be stained using H&E, PAS digest, and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS).Interpretation:

The presence of brown pigmented, branching septate hyphae in any specimen, from a patient with supporting clinical symptoms should be considered significant. Biopsy and evidence of tissue invasion is of particular importance. Remember direct microscopy or histopathology does not offer a specific identification of the causative agent.Note:

Direct microscopy of tissue is necessary to differentiate between chromoblastomycosis which is characterized by the presence in tissue of brown pigmented, planate-dividing, rounded sclerotic bodies and phaeohyphomycosis where the tissue morphology of the causative organism is mycelial.

Cultures showing typical brown, olivaceous black or black colony colour for a dematiaceous hyphomycete.

Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar.Interpretation:

The dematiaceous hyphomycetes involved are well recognized as common environmental airborne contaminants, therefore a positive culture from a non-sterile specimen, such as sputum or skin, needs to be supported by direct microscopic evidence in order to be considered significant. A supporting clinical history in patients with appropriate predisposing conditions, is also helpful. Culture identification is the only reliable means of distinguishing these fungi.Serology:

There are currently no commercially available serological procedures for the diagnosis of any of the infections classified under the term phaeohyphomycosis.Identification:

Culture characteristics and microscopic morphology are important, especially conidial morphology, the arrangement of conidia on the conidiogenous cell and the morphology of the conidiogenous cell. Cellotape flag and/or slide culture preparations are recommended.Causative agents:

Alternaria sp., Aureobasidium pullulans, Cladophialophora bantiana, Verruconis gallopava, Curvularia sp., Exophiala sp., Exserohilum sp., Phialophora verrucosa.Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Ellis MB. 1971 and 1976. Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes and More Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes. International Mycological Institute.

Hoog de GS et al. 1977. The black yeasts and allied hyphomycetes. Studies in Mycology N0. 15 from Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands. CBS publications may be ordered from Tinke van den-Berg-Visser, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, PO Box 273, 3740 AG Baarn, The Netherlands FAX + 31 2154 16142.

Hoog de GS and J Guarro. 1994. Atlas of Clinical Fungi from Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands. CBS publications may be ordered from Tinke van den-Berg-Visser, Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, PO Box 273, 3740 AG Baarn, The Netherlands FAX + 31 2154 16142.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

McGinnis MR. 1980. Laboratory handbook of medical mycology. Academic Press [this is out of print but a copy would be a valuable acquisition].

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co.

Warnock DW and MD Richardson. 1991. Fungal infection in the compromised patient. 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons. -

Rhinosporidiosis

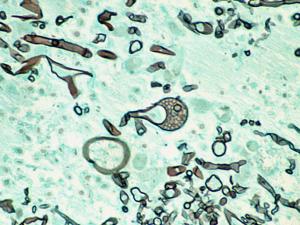

Rhinosporidium seeberi, first described by Malbran in 1892, is the causative agent of rhinosporidiosis, a chronic subcutaneous mycosis. The infection is characterized by formation of polypoid masses at nasal mucosa, conjunctiva, genitalia, and rectum. Fish and aquatic insects are the natural reservoirs of R. seeberi.

The taxonomic classification of R. seeberi has long been controversial so far and has been based solely on morphological properties. Microscopically, R. seeberi produces spherules in infected tissue and these spherules are filled with endospores. Most interestingly, and complicating the issue, this microorganism cannot be cultured in vitro on artificial media. Based on these findings, while some investigators classified it as an ascomycetous fungus, others preferred the term "fungus-like".

Click images below to expand:

The taxonomy of R. seeberi was studied in more detail recently by molecular phylogenetic analysis. Interestingly, the results of these studies revealed that the sequence of 18S SSU rDNA from the R. seeberi isolates of two infected humans, a dog, and a swan proved to be identical to each other and related to a group of fish parasites.

Of note, R. seeberi was placed within the DRIP clade (Dermatocystidium, rosette agent, Ichtyophonus, and Psorospermium) in 1996. DRIP clade was later renamed as the class Ichtyosporea in 1998, and most recently as the class Mesomycetozoea in 2002. The class Mesomycetozoea includes a heterogeneous group of microorganisms that are at the animal-fungal boundary and consists of two orders; Dermocystida and Ichthyophonida.

While the microorganisms included in the order Dermocystida are either pathogens of fish (Dermocystidium spp. and the rosette agent) or of mammals and birds (R. seeberi), those in the order of Ichthyophonida are either pathogens of fish or are saprophytic microorganisms. Thus, R. seeberi now appears as the only microorganism that is classified in the class Mesomycetozoea and is pathogenic to mammals and birds.

Future studies will hopefully provide more information about the morphological features and pathogenicity of R. seeberi.

Related reading

Mendoza L, Taylor JW, Ajello L. The class mesomycetozoea: a heterogeneous group of microorganisms at the animal-fungal boundary. Annu Rev Microbiol 2002;56:315-44.

Herr RA, Mendoza L, Ajello L. Rhinosporidium, is it still a fungus? 9th Congress of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology and 7th Trends in Invasive Fungal Infections-Joint Meeting. September 28-October 1, 2003, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, S10.03.

Herr RA, Ajello L, Taylor JW, Arseculeratne SN, Mendoza L. Phylogenetic analysis of Rhinosporidium seeberi's 18S small-subunit ribosomal DNA groups this pathogen among members of the protoctistan Mesomycetozoa clade. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2750-4.

Fredricks DN, Jolley JA, Lepp PW, Kosek JC, Relman DA. Rhinosporidium seeberi: a human pathogen from a novel group of aquatic protistan parasites. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6: 273-82. -

Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is primarily a chronic mycotic infection of the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues and adjacent lymphatics characterized by nodular lesions which may suppurate and ulcerate. Infections are caused by the traumatic implantation of the fungus into the skin, or very rarely, by inhalation into the lungs. Secondary spread to articular surfaces, bone and muscle is not infrequent, and the infection may also occasionally involve the central nervous system, lungs or genitourinary tract.

Clinical manifestations:

Fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis showing an ulcerating lesion on the leg.

Fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis:

Primary lesions develop at the site of implantation of the fungus, usually at more exposed sites mainly the limbs, hands and fingers. Lesions often start out as a painless nodule which soon become palpable and ulcerate often discharging a serous or purulent fluid. Importantly, lesions remain localised around the initial site of implantation and do not spread along the lymphangitic channels. Isolates from these lesions usually grow well at 35C, but not at 37C.

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis showing typical elevated subcutaneous nodules developing along the regional lymphatics of the forearm.

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis:

Primary lesions develop at the site of implantation of the fungus, but secondary lesions also appear along the lymphangitic channels which follow the same indolent course as the primary lesion ie they start out as painless nodules which soon become palpable and ulcerate. No systemic symptoms are present. Isolates from these lesions usually grow well at both 35C and 37C.

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis showing more advanced, ulcerating lesions developing along the lymph system of the forearm.

Pulmonary sporotrichosis:

This is a rare entity usually caused by the inhalation of conidia but cases of haematogenous dissemination have been reported. Symptoms are nonspecific and include cough, sputum production, fever, weight loss and upper-lobe lesion. Haemoptysis may occur and it can be massive and fatal. The natural course of the lung lesion is gradual progression to death.Osteoarticular sporotrichosis:

Most patients also have cutaneous lesions and present with stiffness and pain in a large joint, usually the knee, elbow, ankle or wrist. Osteomyelitis seldom occurs without arthritis; the lesions usually confined to the long bones near affected joints.Other rare forms of sporotrichoisis include endophthalmitis, chorioretinitis and meningitis.

Section from a fixed cutaneous lesion showing round Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) positive budding yeast-like cells. Sporothrix schenckii is a dimorphic fungus and this is the typical yeast-like form seen in tissue.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

A tissue biopsy is the best specimen.Direct microscopy:

Tissue sections should be stained using PAS digest, Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS) or Gram stain.Interpretation:

Look for small narrow base budding yeast cells (2-5um). Note they are often present in very low numbers and may be difficult to find. PAS and GMS stains are essential.Culture:

Clinical specimens should be inoculated onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar and Brain heart infusion agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood.Interpretation:

A positive culture from a biopsy should be considered significant.Serology:

Serological tests are of limited value in the diagnosis of Sporotrichosis.Identification:

Hyphomycete characterized by thermal dimorphism and clusters of ovoid, denticulate conidia produced sympodially on short conidiophores.Causative agents:

Sporothrix schenckii complex.Further reading:

Ajello L and R.J. Hay. 1997. Medical Mycology Vol 4 Topley & Wilson's Microbiology and Infectious Infections. 9th Edition, Arnold London.

Elewski BE. 1992. Cutaneous fungal infections. Topics in dermatology. Igaku-Shoin, New York and Tokyo.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Richardson MD and DW Warnock. 1993. Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management. Blackwell Scientific Publications, London.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co. -

Zygomycosis

The term zygomycosis describes in the broadest sense any infection due to a member of the Zygomycetes. These are primitive, fast growing, terrestrial, largely saprophytic fungi with a cosmopolitan distribution. To date, some 665 species have been described although infections in humans and animals are generally rare. Medically important orders and genera include: Rhizopus, Lichtheimia, Rhizomucor, Mucor, Cunninghamella, Saksenaea, Apophysomyces, Cokeromyces and Mortierella.

Clinical manifestations:

Zygomycosis in the debilitated patient is the most acute and fulminate fungal infection known. The disease typically involves the rhino-facial-cranial area, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, skin, or less commonly other organ systems. It is often associated with acidotic diabetes, starvation, severe burns, intravenous drug abuse, and other diseases such as leukemia and lymphoma, immunosuppressive therapy, or the use of cytotoxins and corticosteroids, therapy with desferrioxamine (an iron chelating agent for the treatment of iron overload) and other major trauma. The infecting fungi have a predilection for invading vessels of the arterial system, causing embolization and subsequent necrosis of surrounding tissue. A rapid diagnosis is extremely important if management and therapy are to be successful.

Rhinocerebral zygomycosis showing involvement of the palate.

Rhinocerebral zygomycosis:

Predisposing factors include uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or acidosis, steroid induced hyperglycemia, especially in patients with leukemia and lymphoma, renal transplant and concomitant treatment with corticosteroids and azathioprine. Infections usually begin in the paranasal sinuses following the inhalation of sporangiospores and may involve the orbit, palate, face, nose or brain.Pulmonary zygomycosis:

Predisposing conditions include haematological malignancies, lymphoma and leukemia, or severe neutropenia, treatment with cytotoxins and corticosteroids, desferrioxamine therapy; diabetes and organ transplantation. Infections result by inhalation of sporangiospores into the bronchioles and alveoli, leading to pulmonary infraction and necrosis with cavitation.Gastrointestinal zygomycosis:

A rare entity, usually associated with severe malnutrition, particularly in children, and gastrointestinal diseases which disrupt the integrity of the mucosa. Primary infections probable result following the ingestion of fungal elements and usually present as necrotic ulcers.Cutaneous zygomycosis:

Local traumatic implantation of fungal elements through the skin, especially in patients with extensive burns, diabetes or steroid induced hyperglycemia and trauma. Lesions vary considerably in morphology but include plaques, pustules, ulcerations, deep abscesses and ragged necrotic patches.Click images below to expand:

Disseminated zygomycosis:

May originate from any of the above, especially in severely debilitated patients with haematological malignancies, burns, diabetes or uraemia.Central nervous system alone:

Intravenous drug abuse. Traumatic implantation leading to brain abscess.Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Skin scrapings from cutaneous lesions; sputum and needle biopsies from pulmonary lesions; nasal discharges, scrapings and aspirates from sinuses in patients with rhinocerebral lesions; and biopsy tissue from patients with gastrointestinal and/or disseminated disease.Warning: zygomycetous fungi have primitive coenocytic hyphae that will often be damaged and become non-viable during the biopsy procedure (especially scrapings and aspirates), or by the chopping up or tissue grinding process in the laboratory. This is why zygomycetous fungi that are clearly visible in direct microscopic or histopathological mounts are often difficult to grow in culture from clinical specimens. If on clinical and/or radiological evidence zygomycosis is suspected then try to avoid excessive tissue damage when collecting the specimen and in the laboratory gently tease the tissue apart and inoculate it directly onto the isolation media. If you are not sure hold the specimen in saline or BHI broth until the results of the direct microscopy or frozen histology sections are known. If zygomycetous hyphae are present proceed as above, otherwise homogenised the specimen and plate out.

Click images below to expand:

Culture:

Inoculate specimens onto primary isolation media, like Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Most zygomycetes are sensitive to cycloheximide (actidione) and this agent should not be used in culture media. Look for fast growing, white to grey or brownish, downy colonies.Interpretation:

Despite being recognised as common laboratory contaminants, zygomycetes are infrequently isolated in the clinical laboratory. Therefore, in patients with any of the above predisposing conditions, especially diabetes or immunosuppression and/or clinical symptoms, the isolation of any zygomycete fungus should be regarded as potentially significant. Obviously, in patients without predisposing conditions, the isolation of a zygomycete from a non-sterile site, such as skin or sputum, must be interpreted with caution, especially in the absence of direct microscopy.Serology:

There are currently no commercially available serological procedures for the diagnosis of zygomycosis. Although some laboratories have developed ELISA tests for the detection of antibodies to Zygomycetes.Identification:

Zygomycetes are usually fast growing fungi characterised by primitive coenocytic (mostly aseptate) hyphae. Asexual spores include chlamydoconidia, conidia and sporangiospores contained in sporangia borne on simple or branched sporangiophores. Sexual reproduction is isogamous producing a thick-walled sexual resting spore called a zygospore.Most isolates are heterothallic i.e. zygospores are absent, therefore identification is based primarily on sporangial morphology. This includes the arrangement and number of sporangiospores, shape, colour, presence or absence of columellae and apophyses, as well as the arrangement of the sporangiophores and the presence or absence of rhizoids. Growth temperature studies (25,37,45C) can also be helpful. Tease mounts are best, use a drop of 95% alcohol as a wetting agent to reduce air bubbles. Laboratory identification of some zygomycetous fungi, especially Apophysomyces elegans and Saksenaea vasiformis may be difficult or delayed because of the mould's failure to sporulate on the primary isolation media or on subsequent subculture onto potato dextrose agar. Sporulation may be stimulated by the use of nutrient deficient media, like cornmeal-glucose-sucrose-yeast extract agar, Czapek Dox agar, or by using the agar block method on water agar.

Causative agents:

Lichtheimia corymbifera, Apophysomyces elegans, Cunninghamella bertholletiae, Mortierella wolfii, Mucor sp., Rhizomucor pusillus, Rhizopus arrhizus, Rhizopus sp., Saksenaea vasiformis.Further reading:

Ellis, DH. 2005. Systemic Zygomycetes – Mucormycosis. Chapter 33. In Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections: Medical Mycology, 10th edition, Hodder Arnold London. pp 659-686.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co. -

Entomophthoromycosis

Infections caused by entomophthoraceous fungi:

Zygomycosis due to entomophthoraceous fungi:

This is caused by species of two genera Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus. Infections are chronic, slowly progressive and generally restricted to the subcutaneous tissue in otherwise healthy individuals. Other characteristics that separate these infections from those caused by mucoraceous fungi are a lack of vascular invasion or infarction and the production of a prolific chronic inflammatory response, often with eosinophils and Splendore-Hoeppli phenomena around the hyphae.

Zygomycosis caused by Basidiobolus ranarum.

Zygomycosis caused by Basidiobolus ranarum:

This is a chronic inflammatory or granulomatous disease generally restricted to the subcutaneous tissue of the limbs, chest, back or buttocks, primarily occurring in children and with a predominance in males. Initially, lesions appear as subcutaneous nodules which develop into massive, firm, indurated, painless swellings which are freely movable over the underlying muscle, but are attached to the skin which may become hyperpigmented but not ulcerated.

Zygomycosis caused by Conidiobolus (Courtesy of John Rippon, USA).

Zygomycosis caused by Conidiobolus sp.:

This is a chronic inflammatory or granulomatous disease that is typically restricted to the nasal submucosa and characterised by polyps or palpable restricted subcutaneous masses. Clinical variants, including pulmonary and systemic infections have also been described. Human infections occur mainly in adults with a predominance in males (80% of cases). Most cases have been reported from the tropical rain forest areas of central and west and south and central America. Infections usually begin with unilateral involvement of the nasal mucosa. Symptoms include nasal obstruction, drainage and sinus pain. Subcutaneous nodules develop in the nasal and perinasal regions and progressive generalised facial swelling may occur. Infections also occur in horses usually producing extensive nasal polyps and other animals. Conidiobolus coronatus is also a recognised pathogen of termites, other insects and spiders.

H&E stained section of infected tissue showing broad, infrequently septate, hyphae surrounded by an eosinophilic sheath [Splendore-Hoeppli phenomena], typical of zygomycosis caused by Basidiobolus ranarum.

Laboratory diagnosis:

Clinical material:

Skin biopsy tissue.Direct microscopy:

Tissue sections should be stained with H&E and GMS. Examine specimens for broad, infrequently septate, thin-walled hyphae, which often show focal bulbous dilations and irregular branching.Further reading:

Ellis, DH. 2005. Subcutaneous Zygomycetes – Subcutaneous zygomycosis. Chapter 17. In Topley and Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections: Medical Mycology, 10th edition, Hodder Arnold London pp 347-355.

Kwon-Chung KJ and JE Bennett 1992. Medical Mycology Lea & Febiger.

Rippon JW. 1988. Medical Mycology WB Saunders Co.