Are our food systems resilient?

Last week Dr. John Ingram of Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford visited GFAR and gave a seminar to our staff and PhD students on food system resilience. Dr. Ingram is currently in Australia on an OECD fellowship and based at University of Queensland. He is coordinating the UK Global Food Security Programme’s “Resilience of the UK Food System in a Global Context” research program and is spending time in Australia to learn about the Resilience of the Australian Food System.

Degradation of key resources required for agriculture like soil, fresh water, and marine resources has put tremendous pressure on our food systems. A recent study has also found that the biodiversity that is crucial for our food and agriculture is disappearing by the day. Our food systems are also plagued by problems like malnutrition, hidden hunger and over consumption. Studies published in The Lancet have claimed that “there is zero chance that the world can meet the target set by the UN for halting the climbing obesity rate by 2025”. Dr. Ingram in his talk mentioned that, “Governments and institutions have been trying to curb the obesity epidemic but it is on the rise while on the other hand we have improved in bringing down the number of hungry people in the world but there is still a long way to go before the world becomes food secure”.

A systemic approach looking at food systems highlights the role of multiple actors including producers (local, regional and global), food chain actors (post farm gate activities like processing, packaging, trading, shipping, storing, advertising and retailing) and finally consumers (dietary diversity, food preferences, affordability, cooking skills, convenience, cultural considerations). Apart from this, food systems are also expected to generate a particular set of ‘outcomes’ for the society which include socioeconomic outcomes (income, employment, health, social and political capital) and environmental outcomes (combating climate change, water availability, biodiversity conservation).

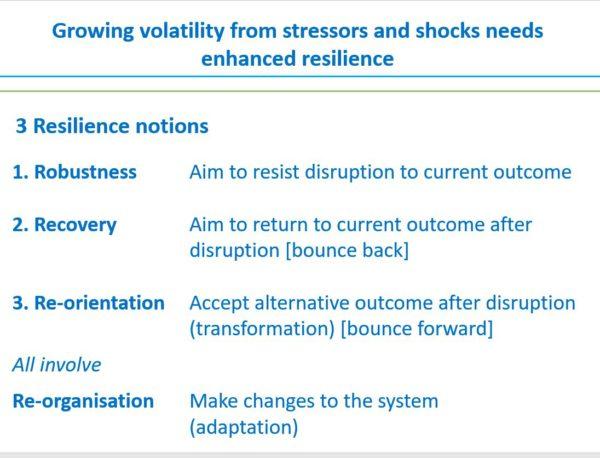

This brings us to the question of how resilient are our food systems currently, to fulfill the basic needs of nourishment and derive the desired outcomes for the society? Dr. Ingram spoke about the notion of resilience and integral aspects to it in his talk. In his view this process involves three key objectives of:

- Robustness – Food systems which are designed to be robust in the sense that current threats to the system are unable to disrupt them and they continue to derive the desired outcomes

- Recovery- Systems designed in a way that they are able to return to normalcy after an event of disruption

- Re-orientation- Systems that are capable of adapting to transformational change and undertake alternative pathways to derive desired outcomes

According to Dr.Ingram, all of these objectives involve Re-Organisation, which involves re-organising our ‘views’ about the food system outcomes requiring a radical transformation of the system which will depend on: better farming methods, wealthy nations consuming less meat and countries valuing food which is nutritious rather than cheap. It also calls for improved coordination between institutions working towards improving the lives of people through a development agenda (FAO, CGIAR, CARE) and institutions working towards improving the health of societies and the environment (WHO, UNEP, WWF).

This conversation is particularly interesting in the Australian context. Australia is a significant exporter of agricultural and food products and has a global reputation of sound environmental and resource management systems. However, recent weather events and rising threat from climate change can put pressure on Australia’s food system and its resilience.

You can follow Dr. Ingram’s work on “Resilience of the UK Food System in a Global Context” here.