Fishing for Data on Plastics

The problem of plastics in our oceans and their potential impact on people, plants, animals and entire ecosystems was front and centre at the recent United Nations Ocean Conference in Portugal.

Through the UN Environment Assembly, more than 500 organisations and 21 additional governments, including Australia, have signed up to commitments to change how plastic is produced, used and reused and through the creation of circular economies to keep it out of the environment.

FRDC has funded a body of research looking at the plastic issue in an Australian context, including a project led by Professor Bronwyn Gillanders at the University of Adelaide, previously featured in FISH magazine.

That project found that seafood species in Australia consume microplastics at low levels in comparison to elsewhere in the world. The average quantity of microplastics was 1.02 pieces per individual Australian finfish, shellfish or squid, which was low compared to the results of many international studies.

Image credit: Nina Wootton

Now Bronwyn’s team is working on a related FRDC project focussed on the potential effects and implications of plastic in seafood and its impacts for fishing and aquaculture. Dr Patrick Reis Santos and Dr Nina Wootton are part of the team reviewing and synthesising available data on sources of marine pollution to quantify how much plastic is entering aquatic ecosystems, including from fishing and aquaculture sources, with a focus on the Australian context. This research will be discussed at the upcoming Plastic Particles and Seafood: Human Health Symposium being held in Edinburgh in September.

“More information is needed so that industry and government can make informed decisions,” Patrick says.

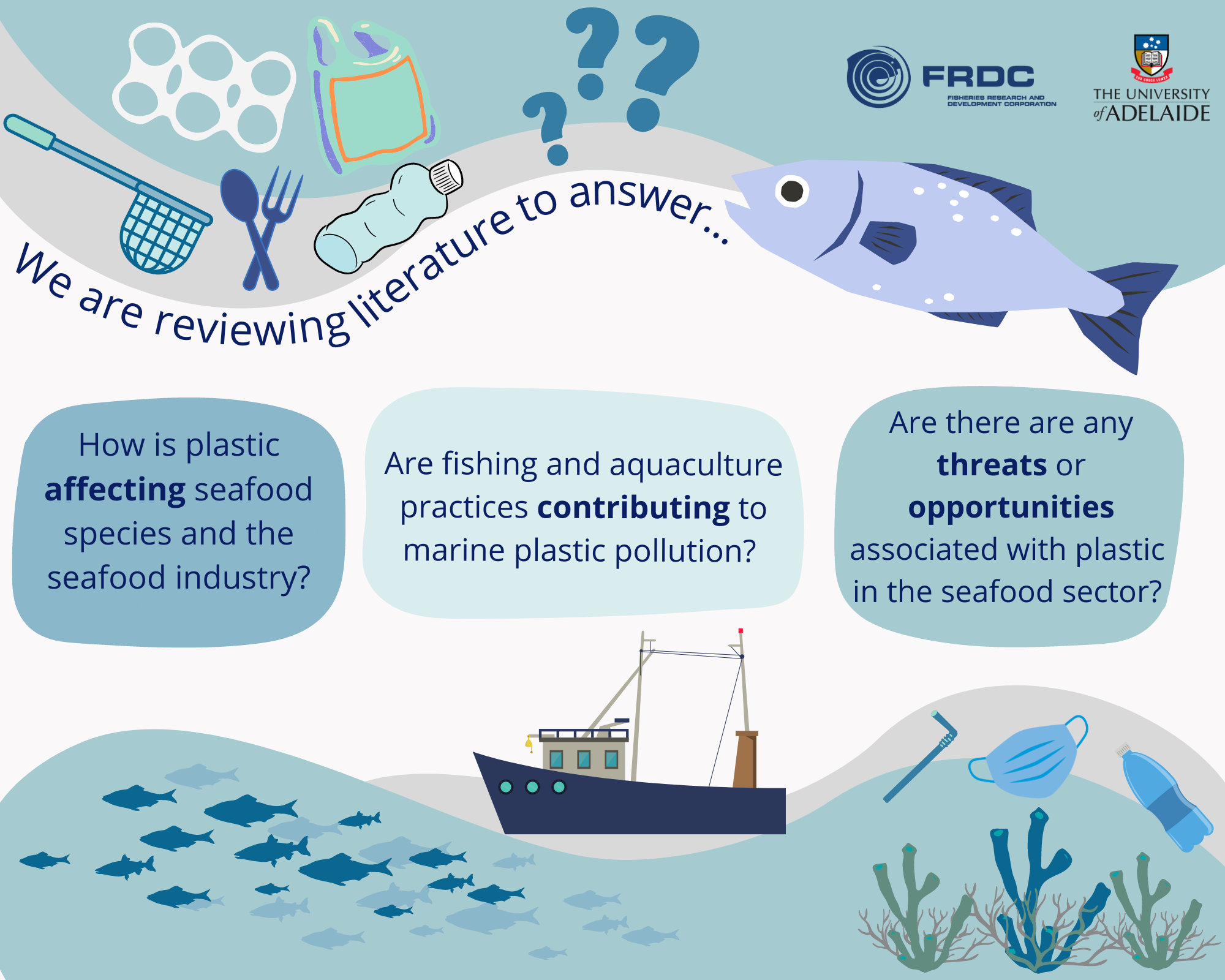

“We’re looking at how plastic is affecting seafood species, if and how fishing and aquaculture practices are contributing to plastic pollution and the associated threats and opportunities,” Patrick says.

“Ultimately, this will give our fishing and aquaculture industries the knowledge to evaluate appropriate mitigation strategies to reduce the presence and impacts of microplastics in seafood.”

Nina says the project is looking beyond the risk to individual animals caused by plastic ingestion or from the chemicals that might leach from plastics.

“We are looking at the known impacts on individual aquatic animals and species and how they could translate to the entire ecosystems and environments they live in,” she says.

“Seafood is just one potential source of plastic contamination for humans – it’s also in water and air and in food and beverage products. “

Patrick says that advances in technology are helping to identify ever smaller plastic particles.

“Now it is possible to detect nanoplastics below one micron in size. We have spectroscopy equipment which can identify the types of plastics and even the brands,” he says.

“In theory, nanoplastics may be small enough to move through the physiological barriers in the human body, for example, through the gut into the bloodstream.”

As part of the project, the team will look for research on how microplastics and nanoplastics are affecting seafood species and humans that consume them.

The project aligns with FRDC’s commitment to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 12 – Initiatives to reduce the production and consumption of plastics.

It also aligns with Australia’s National Plastics Plan to reduce plastic waste and increase recycling; find alternatives to the plastic we don’t need; and reduce the amount of plastic impacting our environment.

For one of the publications that arose from her PhD, Nina and her co-researchers interviewed three groups of stakeholders in South Australia: licensees of the State’s Marine Scale Fishery, which stretches from the Victorian border to the West Australian border; recreational fishers; and fishmongers.

“We found that all three groups thought that the problem of plastics in the marine environment was worse in other parts of Australia or the world, overlooking local sources of pollution” Nina says.

“However, we did find a willingness amongst all sectors to consider using plastic alternatives to fishing gear and relevant packaging.

“There was also agreement that more disposal facilities at boat ramps and marinas would go a long way towards reducing plastic pollution associated with fishing.”

“For fishers, the ocean is their farm, and they want to keep it clean,” Nina says.

This article is republished from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) . Read the original article.

Newsletter & social media

Join us for a sensational mix of news, events and research at the Environment Institute. Find out about new initiatives and share with your friends what's happening.